Victor Alexandru Roncea

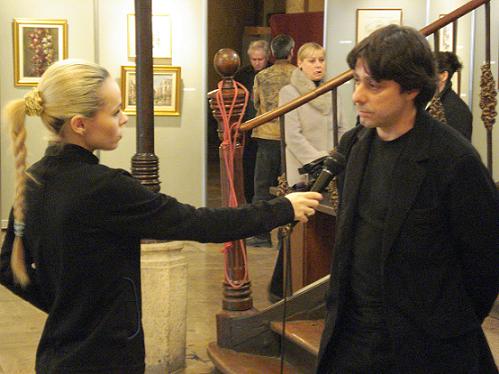

Experienţa în presă:

2020 – Prezent Redactor-șef ActiveNews;

2010 – 2020 Publicist: Evenimentul Zilei, Evenimentul Istoric, Ziarul Bursa; Colaborator: Revista Tribuna, Revista Floare Albastră; Editor: ZIARISTIONLINE.RO si RONCEA.RO

2009 – 2010 CURENTUL – Redactor Sef Adjunct / Editorialist

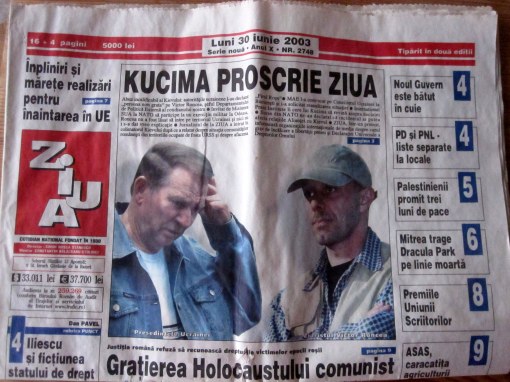

1995 – 2009 ZIUA – Senior Editor / Editorialist / Sef Departament Externe/ Coordonator Suplimente Diplomatice/ Redactor Externe/ Reporter Special

1994-1995 Fotojurnalist/ Corespondent Statele Unite Ziarul ZIUA

1993-1994 „Ultimul Cuvant” – Redactor Externe / Editorialist

1992 – 1993 „Miscarea” – Publicatie a Noii Generatii, membru al Biroului de Presa al Miscarii Pentru Romania

1990-1992 „Romania libera” – Cal mai tanar jurnalist din redactie 🙂 Reporter / Fotoreporter/ Corespondent Statele Unite

1990 „Glasul” – Publicatia Ligii Studentilor, Universitatea Bucuresti – Redactor/Fotoreporter

Debut – Ziarul Golanul – Piata Universitatii 1990, Foto – Expres, Expres Magazin

Specializari: Politica interna si internationala, geopolitica si geostrategie, jurnalism civic si investigatii.

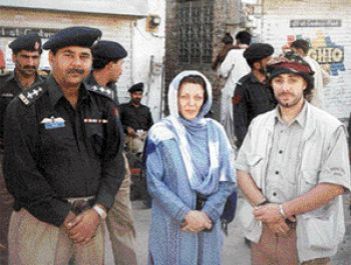

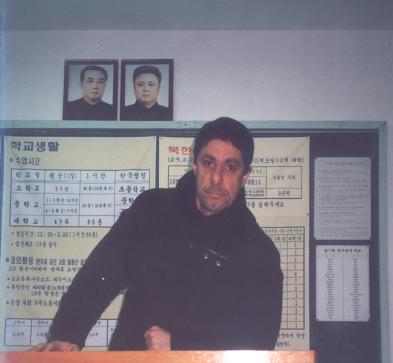

Corespondent in zone de conflict, cum ar fi: fosta Iugoslavie/Bosnia, Serbia, Kosovo, Moldova/Transnistria, Coreea, Pakistan/Afganistan, Irak, Iran, Israel/Palestina, Libia, Sudan, Siria, etc

Corespondent ocazional pentru BBC World Service si BBC Scotland

Înainte de 1989: Arta monumentala: restaurare pictura bisericeasca, mozaic, vitralii

Alte chestii: Functii oferite in administratia de stat si refuzate din dorinta de a ramane jurnalist si om liber, adica muritor de foame (conform exprimarii unui fost demnitar de rang inalt al Romaniei): Sef de Oficiu cu rang de secretar de stat al Oficiului pentru gestionarea relaţiilor cu Republica Moldova din cadrul Guvernului Romaniei aflat in subordinea Primului Ministru si insarcinat si cu presedintia Comitetului Interministerial pentru relaţiile cu Republica Moldova ; sef al Departamentului pentru Relatiile cu Romanii de Pretutindeni din cadrul Ministerului Afacerilor Externe al Romaniei, cu rang de secretar de stat; membru al Consiliul Naţional al Audiovizualului (CNA), cu rang de secretar de stat sau, la alegere, membru al Colegiului CNSAS. De asemenea, consilier/sef de cabinet al unui senator roman si al unui membru al Parlamentului European.

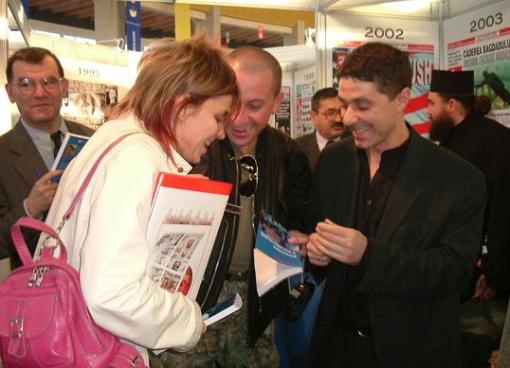

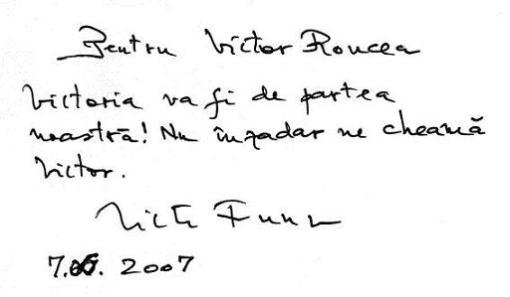

Autor: „Davai Ceas, Davai Traian„, 2007; Editura Tesu; „Romania in noua ordine mondiala”, Editura Ziua, 2004; PĂRINTELE JUSTIN PÂRVU : “De nu ne vom păzi ortodoxia, ne vom pierde şi neamul”, Petru Vodă, 2020

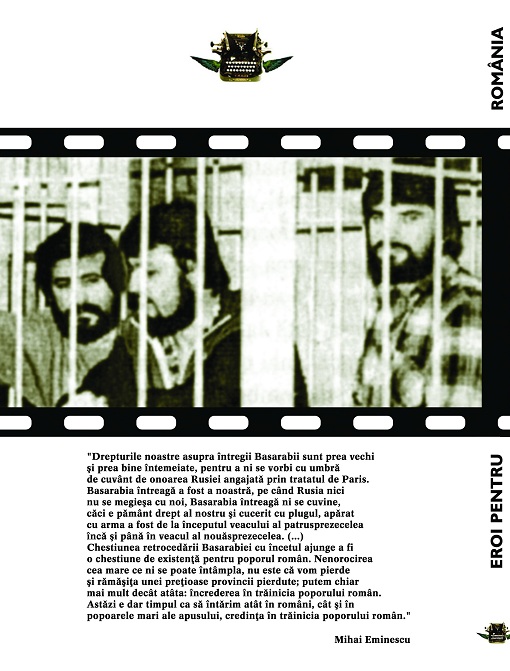

Co-autor si coordonator: „Dictatura Biometrica„, Editori: Fundatia Petru Voda, Asociatia Civic Media, 2009; „NATO’s Eastern Dimension”, NATO Summit Bucharest (www.nato-romania.ro), 2008; „Eroi Pentru Romania„, 2007, Doua Volume – „Transnistria si amenintarile Rusiei la Marea Neagra” si „Brasov 1987 – 15 Noiembrie – Marturii, studii, documente”, impreuna cu Florian Palas si Vladimir Bukovski, Editura Semne; „AXA – Noua Romanie la Marea Neagra”, Editura Ziua, 2005;

Co-autor: „Ostaticii – Drama jurnalistilor. Eliberarea. Operatiunea”, 2005; „Caderea Bagdadului – Irak: Jurnal de razboi”, „100 de ore plus – Irak: Jurnal de razboi”, 2003 – Editura Ziua;

Editor: “MÂNA MOSCOVEI – Documentele crimei din decembrie 1989”, Editura TipoMoldova, 2019

„Parintele Justin Marturisitorul„ de Cristina Nichitus Roncea – Album de fotografii si vorbe de duh, Cuvant Inainte – Aspazia Otel Petrescu, Postfata – Victor Roncea, Editura Mica Valahie, Bucuresti, 2013

ARHIVA NEAGRĂ – Dosarele distrugerii elitei româneşti. Procesul Noica – Pillat, Biblioteca Metropolitana Bucuresti, 2012, impreuna cu profesorul Constantin Barbu si cu sprijinul CNSAS si al Civic Media,

Documente din Arhiva Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, impreuna cu Prof Univ Dr Gheorghe Buzatu si cu sprijinul CNSAS si al Civic Media, Editura TipoMoldova, Iasi, 2012;

Republicarea anastatica a volumului „Omagiu lui Mihai Eminescu” de Corneliu Botez, la 100 de ani de la aparitie, Studiu introductiv – Prof Univ. Dr. Nae Georgescu, Postfata – Victor Roncea, Editura Semne, 2009

Capitolul „Serviciile secrete romanesti dupa 1989 sau Dintr-o reforma in alta” – interviuri realizate cu Gral brig (rez) SRI Aurel I Rogojan, in cartea acestuia, „Fereastra serviciilor secrete. Romania in jocul strategiilor globale”, Editura Compania, 2011

Articol editorial in SIE & SRI – Trecutul nu se prescrie, de Mihai Pelin, 2004

Distinctii: Premiul „Virgil Tatomir” al Uniunii Juristilor din Romania (UJR), pentru „activitatea de presa deosebita pentru Basarabia si Bucovina si in vederea eliberarii detinutilor politic romani din Transnistria”, 2004;

Premiul Special al Presei la Gala Societatii Civile pentru Campania „Solidaritate pentru Delta” – Civic Media, 2004;

Nominalizare „Editorialistul anului 2004” – Clubul Roman de Presa, 2005;

Premiul „Editorialistul anului 2005” al Clubului Roman de Presa (CRP), 2006;

Diploma de onoare si Medalia de merit „pentru promovarea deontologiei profesionale” din partea UJR, 2006;

Premiul „Vocea Basarabiei” conferit de trustul media cu acelasi nume din Republica Moldova, 2006;

Medalia de merit din partea Asociatiei 15 Noiembrie 1987 – Brasov, la comemorarea a 20 de ani de la revolta anticomunista a muncitorilor brasoveni, 2007;

„Ordinul Ziaristilor” Clasa I (aur) din partea Uniunii Ziaristilor Profesionisti din Romania, „pentru valoare si competenta in activitatea jurnalistica”, 2007;

Premiul Uniunii Ziaristilor Profesionisti pentru carte de presa – „Eroi pentru Romania”, 2008;

Diploma de Excelenta din partea Comandamentului National pentru Securitatea Summitului NATO, „pentru contributia exceptionala in sprijinul Summitul-ui NATO desfasurat in Bucuresti, Romania”, conferita de directorul SPP, Gral maior dr Lucian Silvian Pahontu, 2008;

Premiul „Pentru Jurnalism Civic” si „Jurnalistul Anului” din partea Fundatiei Mihai Eminescu, 2008/2009;

Diploma de Onoare din partea Ambasadei Georgiei in Romania si Republica Moldova, „pentru profesionalism, onoare si curaj in sustinerea adevarului, pentru responsabilitate civica si pentru compasiune fata de drama poporului georgian in timpul conflictului Rusia-Georgia din august 2008”, 2009;

Medalia comemorativa „Dimitrie Cantemir” a Fundatiei Culturale Magazin Istoric, „in semn de pretuire pentru activitatea de cercetare si promovare a istoriei si civilizatiei romanilor din jurul Romaniei”, 1 decembrie 2009;

Diploma de Onoare din partea Institutului National pentru Studiul Totalitarismului (INST) al Academiei Romane, „pentru contributia adusa la scoaterea la lumina a secretelor perioadei comuniste din Romania”, 2009;

Diploma Fundatiei Panteonul Romaniei, aflata sub egida Academiei Romane, 2009

Societatea Culturala ART EMIS – Diploma de Excelenta pentru activitatea jurnalistic a anului 2011 ca editor al portalului Ziaristi Online, Evenimentul „Basarabia 200”, organizat de Societatea Culturala ART EMIS si Arhiepiscopia Ramnicului, 2012

Uniunea Ziariştilor Profesionişti din România – Premiile anului 2012: PRESĂ SCRISĂ ȘI ON LINE. TEMA: Reportajul, ancheta publicistică şi articolul de atitudine în slujba promovării/apărării identităţii culturale a comunităţilor româneşti, din afara fruntariilor României.

Premiul I – Cristina Nichitus Roncea și Victor Roncea, Basarabia-Bucovina.Info, Bucuresti, pentru foto-reportajele

Incursiune in Transnistria. Azi: Tighina vazuta de Basarabia-Bucovina.Info. EXCLUSIV si

Premiul „Eminescu, ziaristul„, conferit in premiera de UZPR, pe 28 iunie 2013, la Muzeul National al Literaturii Romane

Premiul special “De la Nistru pan’ la Tisa“ conferit de Asociaţia Jurnaliştilor şi Scriitorilor de Turism din România pe 15 ianuarie 2014, Ziua lui Eminescu

Diploma „Personalitate a anului 2013” acordata la Chișinău, pe 24 ianuarie 2014, cu ocazia aniversarii Unirii Principatelor Române, de Asociatia „Rasaritul Romanesc” din Basarabia „pentru aportul deosebit, constant și eficient adus cauzei românești prin scris și atitudine publicistică exemplară”.

Diploma de Merit INST – Academia Romana pentru proiectul Basarabia-Bucovina.Info, 2014

Menționarea cu un citat despre Serviciul Român de Informaţii în capitolul “SRI văzut de jurnalişti” al lucrarii “Monografia SRI – 25 de ani”, publicată de Editura Rao şi primită prin amabilitatea directorului SRI

Scrisoarea oficială de mulțumire a Patriarhiei Române pentru opiniile exprimate în favoare construirii Catedralei Mântuirii Neamului, 2016

Scrisoarea oficială de mulțumire a Excelenței Sale Giorgi Margvelashvili, Președintele Georgiei, adresată jurnalistului Victor Roncea la 10 ani de la agresiunea Rusiei asupra Georgiei, pentru activitatea în slujba adevărului și solidaritatea cu poporul georgian, August 2018

Diploma și Medalia Jubiliară a Centenarului Marii Uniri din partea Centrului Cultural Spiritul Văratic, Primăria Agapia și Mănăstirea Văratic, „pentru deosebita implicare în acțiunile de promovare a valorilor neamului, pe baricada dreptății în spiritul informării juste a cetățenilor”, 2018

Medalia aniversară România Mare la Centenarul Marii Uniri conferită la Academia Română de către Institutul Național pentru Studiul Totalitarismului în cadrul Conferinței INST 25, pentru susținerea idealului Unității Naționale și sprijinul acordat în ultimul deceniu de activitate, 2018

Premiul Uniunii Ziariştilor Profesionişti din România pe anul 2018 la categoria Presă scrisă pentru seria de interviuri din ziarul BURSA intitulată „Luminile şi umbrele Centenarului”, 2019

Premiul „Pr. Prof. Dr. Ilie Moldovan”, 2020, conferit de Centrul European de Studii Covasna-Harghita al Academiei Române, Forumul Civic al Românilor din Covasna, Harghita și Mureș și Episcopia Covasnei și Harghitei, „în semn de prețuire și recunoștință în sprijinirea Bisericii Ortodoxe, a școlilor în limba română și a instituțiilor de cultură românești din județele Covasna, Harghita și Mureș, în cadrul Proiectului Români pentru Români” și „pentru publiciştii care au relatat cu obiectivitate şi consecvenţă problematica specifică a dăinuirii româneşti în cele trei judeţe şi a convieţuirii interetnice româno-maghiare din zonă” (InfoHr)

Diploma de onoare din partea Academiei Tomitane și Medalia „Sf. Dionisie Exiguul” din partea Arhiepiscopiei Tomisului, de Sărbătoarea Floriilor, 2021

Distincția Credință și Loialitate, oferită de UZPR în 2021, de Ziua Ziaristului Român

Coordonator, membru fondator si membru: Asociatia Civic Media, Organizatia de Media a Sud Estului Europei (South East Europe Media Organization – SEEMO), Conventia Organizatiilor de Media din Romania (COM), Asociatia Jurnalistilor Europeni, Centrul Rezistentei Anticomuniste, Fundatia Pentru Romania, Fundatia Panteonul Romaniei – Academia Romana, Federatia Internationala a Jurnalistilor (FIJ), Federatia Europeana a Jurnalistilor (FEJ), Sindicatul Jurnalistilor Profesionisti, Uniunea Ziaristilor Profesionisti din Romania, Asociaţia Jurnaliştilor şi Scriitorilor de Turism din România, National Geographic Society (1992)

Membru de onoare: Societatea Culturala „Tinutul Herta”; Asociatia „Altermedia”; Asociatia “15 Noiembrie, Brasov – 1987” – Calitate conferita de Vladimir Bukovski cu ocazia Conferintei internationale privind crimele comunismului, Brasov, 2006, In Memoriam Ion Gavrila Ogoranu; Centrul Cultural Spiritual Văratic

Burse si cursuri de jurnalism in: Statele Unite, Marea Britanie, Germania, Austria, Franta, Belgia, Polonia, Ungaria, Slovacia, Serbia, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Albania, la Parlamentul European si NATO, s.a.m.d

Duhovnici si indrumatori: Parintele Teoctist, Parintele Sofian Boghiu, Parintele Adrian Fageteanu, Parintele Gheorghe Calciu, Parintele Constantin Voicescu, Parintele Ioanichie Balan, Parintele Justin Parvu

Politica: Romania

Alte activitati profesionale:

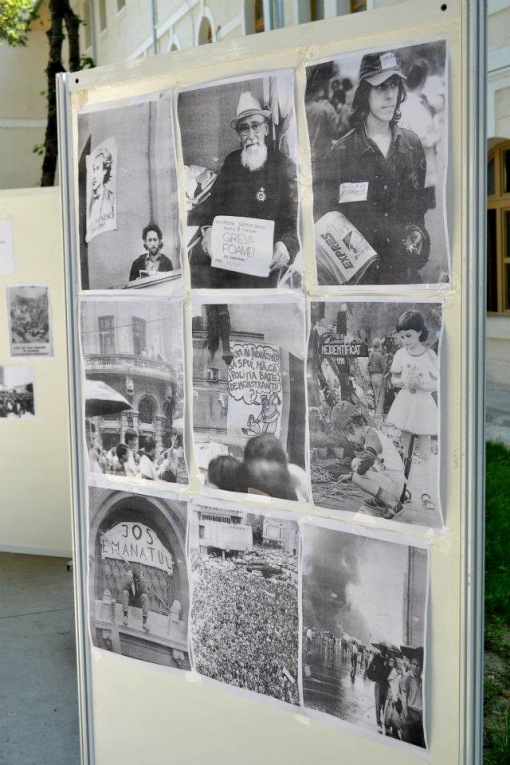

FOTO/FILM: Expozitia de grup itineranta, cu fotografii documentare, intitulata „Romania Inside/Out” – New School for Social Research, New York, NY; The Herbert Hoover Institution on War, Peace and Revolution – Stanford University, California si Chicago Public Library, SUA (1992 – 1993) apoi– Cottbus Film Festival, Germania, 1999;

Expozitia fotografica “Ziua a Treisprezecea” – Galeriile Teatrului National – ArtExpo, vernisata de Parintele Constantin Galeriu, iunie 1997;

“Intoarcerea lui Alexandru”– Film documentar despre eliberarea lui Alexandru Lesco, fost detinut politic in Transnistria timp de 12 ani, difuzat la TVR, Antena 1 si Prima TV, 2004;

Cinema in Transition – East and Central European Film Festival, New York – Primul Festival de Film Est European din SUA de dupa caderea cortinei de fier – Asistent al coordonatorului, 1993;

Fotografii de coperta: Piata Universitatii 1990 – de Romulus Cristea, Editura FOC – Filocalia, in parteneriat cu Editura romano-engleza Karta-Graphic, 2007; Iranul la rece – de Corneliu Vlad, Editura Top-Form, 2011, Revista Arhivele Totalitarismului, Institutul National pentru Studiul Totalitarismului – Academia Romana, 2013

Fotografii in: Istoria Romanilor – de acad. Ioan-Aurel Pop, Editura Litera, Bucuresti, 2011; Enciclopedia regimului comunist, INST – Academia Romana, 2012 – 2013; Arhiva The Herbert Hoover Institution on War, Peace and Revolution – Stanford University

Activitati Civice/Educative:

Expulzat din Ucraina, declarat persona non-grata cu interdictie de intrare timp de 5 ani cu prelungire inca 5 ani pentru activitate jurnalistica in apararea comunitatilor romanesti din spatiul istoric romanesc (Protestul World Association of Newspapers aici);

Procese intentate pentru editoriale din ZIUA de Gabriel Liiceanu si Mihnea Berindei, castigate de Casa de Avocatura Tuca Zbarcea & Asociatii, si un al treilea proces pentru „delict de presa” intentat de Horia Roman Patapievici si castigat in numele meu si al lui „Luca Iliescu” de avocatul George Papu;

Pentru un alt editorial – „Limba lui Ungureanu„, un grup de monolog social (GDS) a cerut eliminarea mea din presa;

Campanii de presa mai importante: Adevarul despre Moartea Patriarhului – vezi si Civic Media; Dosarul Eminescu; Afacerea Gojdu; Afacerea Transchem; Scandalul “Firul Rosu”; Santaj la Seful ANI; Raportul Tismaneanu contra Romaniei; Canalul Bistroe; Romania din jurul Romaniei; Geopolitica Marii Negre – Istmul Ponto-Baltic; Ultimii Romani – Romanii din Harghita-Covasna; Operatiunea „Voci Curate”; Deconspiratii; “Esti in carti cu Iliescu-KGB“; Personalitati pentru pastrarea Icoanelor in Scoli; Salvarea Catedralei Sf Iosif; Actiuni Civice

Despre 21 decembrie 1989: Ziaristi la revolutie. Victor Roncea: Batranul si steagul

Despre mineriada din iunie 1990: Infernul se numeste Magurele

Despre relatia cu Securitatea: Despre presa si securitate, dintr-o perspectiva personala. Discursul lui Victor Roncea sustinut la Universitatea din Oradea, Aula “Nicolae Iorga”, la lansarea cartii generalului Aurel I Rogojan, “Fereastra Serviciilor Secrete”

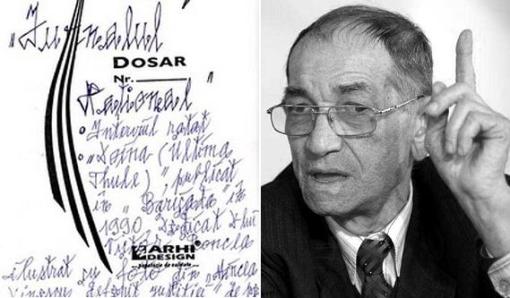

L-am dovedit pe Pacepa „agent al politiei politice comuniste” – DOC CNSAS

Co-organizator al unei serii de conferinte la Facultatea de Sociologie a Universitatii Bucuresti, sub egida Masterului de Studii de Securitate si a Centrului de Geopolitica si Antropologie Vizuala al Universitatii, cu urmatoarele teme, printre altele:

Rolul noii Romanii in noua ordine mondiala – cu participarea ambasadorilor Marii Britanii, Germaniei si Frantei; Transnistria si incalcarile drepturilor omului in Republica Moldova – cu participarea lui Alexandru Lesco; Noile directii ale politicii externe romanesti – cu participarea presedintelui Traian Basescu; Axa – Noua Romanie la Marea Neagra, cu participarea reprezentantilor ambasadelor SUA, Mari Britanii si Germaniei si ai Presedintiei Romaniei; „Ai cui sunt romanii din jurul Romaniei? – Solutii, probleme, provocari” – Raportul societatii civile privind relatia Romaniei cu Romania din afara granitelor, cu participarea, printre altii, a prof dr Gheorghe Zbuchea, Universitatea Bucuresti, pr Radu Ilas, profesor Universitatea din Cernauti, col (r) Cristian Scarlat, Oficiul National pentru Cultul Eroilor, Eugen Tomac, consilier al Presedintelui Romaniei pentru relatiile cu romanii de pretutindeni; Basarabia – 90 de ani de la Unire – cu participarea primarului de la Chisinau Dorin Chirtoaca si a fostului sef al SIE, istoricul Ioan Talpes; Patrimoniul national in pericol – cu participarea primarului general de atunci, Adriean Videanu, a academicianului Dinu C Giurescu si a Reprezentantului Comisiei Europene; Adevarul despre decembrie 1989 – cu participarea lui Alex Mihai Stoenescu; 15 noiembrie – 20 de ani de la revolta anticomunista – cu participarea membrilor Asociatiei 15 noiembrie 1987 – Brasov; Lumea vazuta de la Bucuresti – Kosovo si Romania, cu participarea mai multor corespondenti de razboi; Al cui e Raportul Tismaneanu? cu participarea acad prof dr Dinu C Giurescu si a numeroase cadre academice; Legea lui Eminescu – Aniversarea 120, cu participarea eminescologilor Nae Georgescu, Theodor Codreanu, Constantin Barbu, a studentilor si conducerii Facultatii de Sociologie a Universitatii Bucuresti; Pericolele Televiziunii – cu participarea autorului Virgiliu Gheorghe si a profesorului univ dr Ilie Badescu; Pentru Eminescu, impreuna cu Institutul de Sociologie al Academiei Romane si Fundatia Pentru Romania, 2010, cu participarea eminescologilor si a lui Grigore Lese; Comemorare la mormantul lui Eminescu, 2011; Co-organizator, impreuna cu Civic Media si Institutul de Sociologie al Academiei Romane: Conferinta istoricului american prof. dr. Larry Watts, “Misapprehending Romania: The Role of Cognitive Bias, Institutional Pathologies, and Disinformation”, desfasurata pe 10 mai 2012 la Casa Academiei Romane; Conferinta Dr. Larry Watts la Institutul de Sociologie al Academiei Romane –Perceperea internațională a României în perioada 1978 – 1989 – sept. 2013; Conferinţa aniversară “Basarabia şi Aliaţii incompatibili” cu prof. dr. Larry Watts şi prof. dr. Ilie Bădescu, la Casa Academiei Române – 27 Martie, 2014; “Şcoala Sociologică de la Bucureşti şi întregirea statului român”- Conferinţa din 27 Martie 2015 de la Institutul de Sociologie al Academiei Române; Conferinta de Centenar – Cărțile Centenarului la Institutul de Sociologie al Academiei cu profesorul Ilie Bădescu, dr. Larry Watts și invitații săi – 29 noiembrie 2018, s.a.m.d.

Solicitant catre Presedintele Romaniei pentru reconsiderarea cazurilor Eroilor USLA din Grupul Trosca, 2011

Infiintarea Premiului In Memoriam Mile Carpenisan – Premiul „Mile Carpenisan” pentru Curaj si Excelenta in Jurnalism, in valoare de 1000 Euro, oferit anual de Asociatia Civic Media de Ziua Libertatii Presei, 2010

Co-fondator al „Coalitiei pentru Respectarea Sentimentului Religios„, prin care Asociatia Pro Vita si Asociatia Civic Media au reusit pastrarea icoanelor in scolile din Romania, ca finalitate a Campaniei Salvati Icoanele Copiilor prin sentinta definitiva la Inalta Curte de Casatie si Justitie, data in 22.05.2009, dupa trei ani de procese cu CNCD – vezi Salvati-Icoanele.Info

Co-organizator „90 de ani de la proclamarea Unirii Basarabiei cu Tara – Bucuresti si Chisinau impreuna in Europa„, Comemorari Manastirea Cernica, Conferinta Arcub, Spectacol Piata Universitatii – manifestari desfasurate sub Inaltul Patronaj al Presedintelui Romaniei, Traian Basescu, 27 martie 2008

Decernare de premii pentru presa si societatea civila romaneasca si organizarea Expozitiei de fotografii “Razboiul din Georgia asa cum a fost” – Muzeul de Istorie si Arta al Municipiului Bucuresti – Palatul Sutu si Targul de carte si presa GAUDEAMUS, Fundatia Pentru Romania in colaborare cu Ambasada Georgiei la Bucuresti, noiembrie 2008

Sustinator al manifestatiei din 19 aprilie 2007, din Piata Universitatii, impotriva suspendarii presedintelui Romaniei, Traian Basescu (teapa mea)

Primirea binecuvantarii Prea Fericitului Parinte Teoctist, Patriarh al Bisericii Ortodoxe Romane, pentru proiectul Miscarea de Reintregire a Romaniei, anuntata public la conferinta “BASARABIA ACUM – situatia relatiilor romano-romane la 89 de ani de la Actul Unirii”, incheiata cu Rezulutia Adunarii de la Universitate, 27 martie 2007;

Initiator al campaniei „Voci Curate”, de deconspirare a agentilor serviciilor secrete ale Pactului de la Varsovia si ai politiei politice din societatea civila si mass-media din Romania, realizata prin intermediul Civic Media si CNSAS, 2007;

Protocol parafat de Asociatia Civic Media cu Ministerul Culturii pentru un Muzeu al Comunismului in Romania si initiator si co-organizator al Expozitiei „Epoca de Aur – Intre Propaganda si Realitate” – Muzeul National de Istorie a Romaniei, ianuarie 2007;

Solicitant al conferirii de catre Presedintele Romaniei, Traian Basescu, a Ordinului National „Steaua Romaniei” pentru fostii detinuti politic de la Tiraspol Alexandru Lesco, Tudor Popa si Andrei Ivantoc si a titlului de Cetatean de Onoare al Orasului Bucuresti de catre Primarul General al Capitalei, Adriean Videanu, 2007;

Initierea si coordonarea campaniilor pentru eliberarea prizonierilor politici de la Tiraspol, ajutorarea copiilor din Transnistria, protejarea Deltei Dunarii de agresiunea Ucrainei asupra mediului prin construirea canalului Bistroe; Campanii Ziua – Civic Media 2004-2005;

Membru al echipei de cercetari a Ligii Studentilor privind crimele, brutalizarile, disparitiile si arestarile ilegale din iunie 1990;

Co-organizator al manifestatiei-maraton cunoscuta sub numele de „Fenomenul Piata Universitatii”, 1990 (Vezi si Eu sunt nebunul care a blocat Piata Universitatii. ZIUA deschiderii balconului: 24 aprilie 1990)

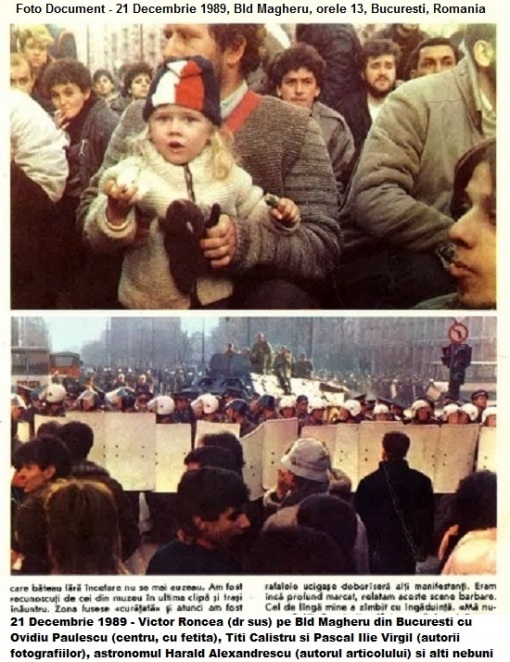

Participant la revolta anticomunista din decembrie 1989, incepand cu 21 decembrie, in Bucuresti (fara a solicita nici un beneficiu ulterior – Vezi Cum mi-am petrecut sfarsitul comunismului cu nebunii lui 21 Decembrie 1989. Foto-document: Ovidiu Paulescu, Harald Alexandrescu, Titi Calistru, Pascal Ilie Virgil, Victor Roncea si alti (cativa) nebuni. Evocare Ernest Maftei: Batranul si Steagul si Cum l-am intalnit pe Mos Craciun la revolutie impreuna cu Cristian Botez)

In continuare, cateva dintre participarile la cursuri si seminarii internationale, in limba engleza:

Human Rights rapportor for Helsinki Watch, Amnesty International and Freedom House, 1991

Speaker at the Amnesty International Berlin’s yearly branch meeting, 1991

National Prayer Breakfast (Washington DC) representant of Romania’s youth civic movement, 1992

OSCE elections observer in Republic of Moldova (Bessarabia), 1998

Speaker at the “Democratic Youth Camp”’ for SEE, organized in Hungary by the Stability Pact, 1999

Election observer at the Presidentials of Russian Federation, 2000

Stability Pact Media Task Force participant for observing the elections in Albania, 2000

Co-Founder of Civic Media Association eu.ro.21 (http://www.civicmedia.ro), 2000

Co-Founder of South East Europe Media Organization (SEEMO),

affiliated to International Press Institute (IPI), founded in New York and based in Vienna, 2000

· Civic Media Association’ observer for elections in: Bosnia-Hertzegovina, Yugoslavia and Moldova, 2000

· “Election UK 2001” – participant in a British Council’ program for shadowing the elections, 2001

· “The role of journalist organizations in SEE” – Seminar jointly organized by the International Institute for Journalism (IIJ) of teh German Foundation for International Development (DS) and the Media Development Center (MDC), Sofia, 2001

· ACM’ Observer for Parliamentary Elections in Kosovo, 2001

· “Regionalisation of Serbia” – Seminar of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities/Council of Europe – Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 2001

· “Danger: Spin Doctors at Work” – courses of British Association for Central and Eastern Europe (BACEE), London, 2002

· “Together in a Commune Europe” – international seminar organized by Kondrad Adenauer Foundation and Institute for Democracy in Eastern Europe (IDEE), Warsaw, Poland, 2002

· “South Eastern Europe – a European Perspective” – international seminar organized by Robert Schuman Foundation, Sofia, Bulgaria, 2002

· “Europe before Unification” – European journalists seminar organized by European Academy Berlin and the Foreign Affaires Ministeries of Germany, France and Slovakia, Bratislava, 2002

· Final Enlargment Debate – European Parliament, Strasbourg, 2002

· “NATO and East-European Opinion Formers”, NATO Press and Information Office, Bruxelles, 2003

· “Black Sea Area and the New NATO”, seminar organized by US Mission to NATO, Bruxelles, 2003

· “Journalists of the New Europe” – seminar organized in Berlin by European Academy Berlin, 2003

· “The World after Iraq” – International Press Institute and SEEMO conference, Austria, 2003

· “Journalists Rights”, speaker at the seminar organized in Bucharest by Romanian Press Club, Council of Europe and Stability Pact for South East Europe, 2003

· Co-founder of Convention of Media Organization from Romania (COM), 2003

· “Journalists Status in Romania”, seminar organized by COM and founded by European Union, 2004

· Coordinator of a National and International campaign for the released of the Romanian political prisoners from Transdnister separatist republic, Moldova – 140 organizations with 4.000.000 members, 2004

· Co-founder of Romanian Civic Initiative, a fora of around 140 NGO and institutions, 2004

· Coordinator of Stop the Distruction of Danube Delta – National and International campaign, 2004

· Co-founder of Coalition for the Danube Delta, 2004

· Black Sea Security Program – The Norvegian Nord-Atlantic Committee and Casa NATO, 2004

· „News to Know: introducing democratic media to schools in Romania” – US Embassy and Romanian Youth League programme under the auspicies of HE Jack Dyer Crouch II, 2004-2005.

· “Romania in the new world order” – University of Bucharest, ZIUA, ACM international conference, 2005

· Media and the Democratization Process in Moldova and Black Sea Area, ACM, Timisoara, 2005

· European Newspaper Congress, Vienna, 2005

· Assigned to register the new Association of European Journalists, Romania, 2005

· „The New Directions of the Romanian Foreign Policy” – Special Speaker: Traian Basescu, President of Romania – University of Bucharest, Center of Geopolitics, ZIUA, ACM conference, 2005

· Enlargement 2007 – Bulgaria and Romania in the EU/Black Sea Area – Academy of the Konrad – Adenauer Stiftung, German-Bulgarian-Romanian expert discussion in cooperation with the Planning Staff of the German Foreign Ministry

· ACM observer of elections in Republica of Moldova, 2009

· Federal Foreign Office Bloggers & Journalists Tour of Germany, 2011

Trebuie să fii autentificat pentru a publica un comentariu.